Rural deep South faces digital divide and doctor shortage driving heart disease crisis

Counties with lower densities of primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and cardiovascular specialists consistently experienced higher CHD death rates. A critical finding was the statistically significant association between digital exclusion, measured by households lacking access to a computer or smartphone, and higher CHD mortality. In contrast, broadband access itself was not a significant predictor of mortality, suggesting that household-level technology access, rather than regional connectivity alone, is more essential for realizing the benefits of telehealth.

- Country:

- United States

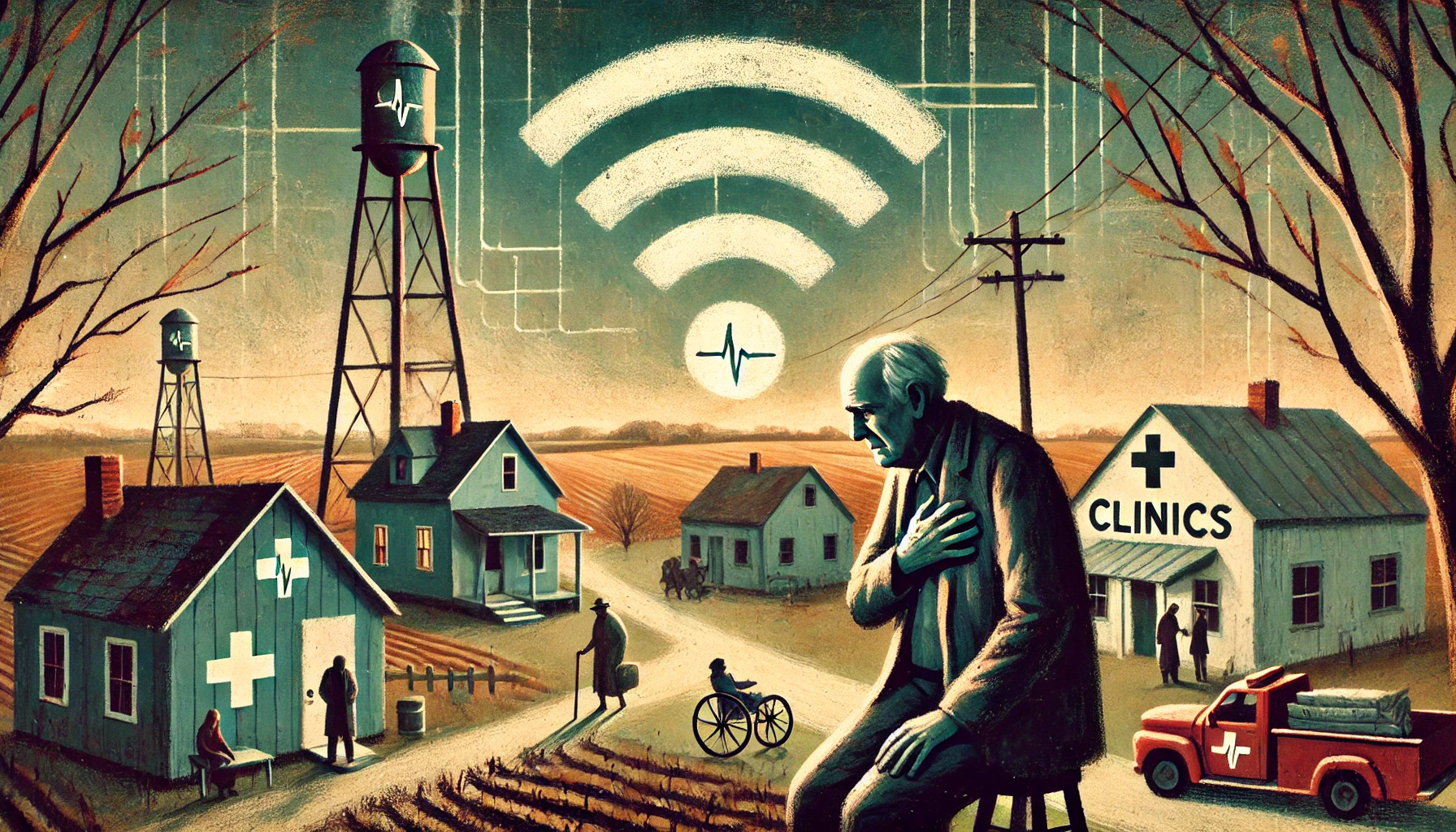

A new study warns that rural counties across the Deep South face a disproportionate burden of coronary heart disease (CHD), driven by a complex web of digital exclusion, healthcare access shortages, and socioeconomic vulnerabilities. The study, titled "Telehealth-Readiness, Healthcare Access, and Cardiovascular Health in the Deep South: A Spatial Perspective" and published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, reveals stark spatial patterns and structural determinants that help explain why some of the most underserved communities in Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina remain epicenters of cardiovascular mortality.

How do provider shortages and digital exclusion affect CHD outcomes?

The study analyzed data from 418 counties across the Deep South, using spatial clustering techniques and multivariable regression models grounded in the Andersen healthcare utilization model. It identified “hotspots” where CHD mortality and prevalence rates were alarmingly high, particularly in counties characterized by severe provider shortages, digital infrastructure gaps, and limited socioeconomic resources.

Counties with lower densities of primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and cardiovascular specialists consistently experienced higher CHD death rates. A critical finding was the statistically significant association between digital exclusion, measured by households lacking access to a computer or smartphone, and higher CHD mortality. In contrast, broadband access itself was not a significant predictor of mortality, suggesting that household-level technology access, rather than regional connectivity alone, is more essential for realizing the benefits of telehealth.

Preventable hospitalizations also emerged as a strong indicator of healthcare system strain, positively correlating with CHD death rates. These patterns underscore that without physical provider access and baseline digital readiness, telehealth cannot fulfill its promise to close health gaps in rural America.

Who is most at risk in these rural communities?

Predisposing demographic characteristics, including age and rural residency, were also closely linked to poorer cardiovascular outcomes. The study found that counties with higher proportions of residents aged 65 and older faced significantly elevated CHD death and diagnosis rates. These populations require more frequent medical interventions and are particularly vulnerable in the absence of robust preventive care infrastructure.

Further, counties with a higher percentage of non-Hispanic White residents and greater rurality also demonstrated higher CHD prevalence. Rurality, in this context, was not merely a geographic label but a marker for systemic disadvantage—encompassing long travel distances to care, fewer hospitals, transportation scarcity, and higher rates of uninsurance.

The mean percentage of households without a vehicle reached nearly 7% across these counties, and this transportation gap was significantly correlated with higher CHD prevalence. This finding supports the argument that without mobility, residents struggle to access even the most basic healthcare services, let alone specialized or preventive care for chronic conditions like CHD.

What resources help protect against poor cardiovascular health?

While many counties suffered from cumulative disadvantages, the study also identified several enabling resources that offered protective effects. Chief among them was provider availability: a higher number of primary care physicians per capita was associated with significantly lower rates of both CHD diagnosis and mortality. This affirms the importance of investing in the healthcare workforce in rural areas, particularly in preventive and chronic disease management roles.

Median household income also emerged as a robust protective factor. Higher income levels were associated with lower CHD mortality and prevalence, likely reflecting broader access to resources that facilitate healthcare engagement, such as transportation, insurance coverage, and nutritional food options. In effect, economic capital enabled greater health capital.

Interestingly, while general broadband access was not directly associated with reduced CHD mortality, the presence of household-level computing devices was strongly protective. This suggests that digital readiness goes beyond mere infrastructure to include the tools and competencies required for telehealth engagement. Counties with high rates of households lacking digital devices exhibited higher rates of both CHD prevalence and death.

Notably, the study also identified outlier counties that defied expectations. Despite facing structural disadvantages, such as high rurality, low provider density, and limited digital access, some counties demonstrated lower-than-expected CHD outcomes. Examples include Washington County, Alabama and Treutlen County, Georgia. These areas may benefit from unmeasured resilience factors, such as strong community networks, local health initiatives, or effective public health partnerships. Their relative success underscores the need for future research into localized innovations and informal health support systems.

Policy implications and next steps

The findings present a clear mandate for targeted, multi-sector investment in rural health equity. Digital inclusion must be expanded in tandem with physical healthcare infrastructure. Policies should incentivize provider retention in rural areas, invest in mobile health units, and promote digital literacy and access through subsidized device distribution.

Hybrid care models, that integrate virtual platforms with community-based services, are urgently needed in regions where standalone telehealth may be unfeasible. Public health strategies should account for both macro-level structural inequalities and micro-level community resilience. For example, promoting rural residency training programs and loan forgiveness for healthcare professionals in underserved areas could improve provider density over time.

The study cautions that while the Andersen model provides a useful framework for understanding access and outcomes, it does not fully capture resilience or social capital, factors that may explain unexpectedly positive outcomes in certain counties. Therefore, future studies should explore the role of informal networks and locally driven interventions.

- FIRST PUBLISHED IN:

- Devdiscourse