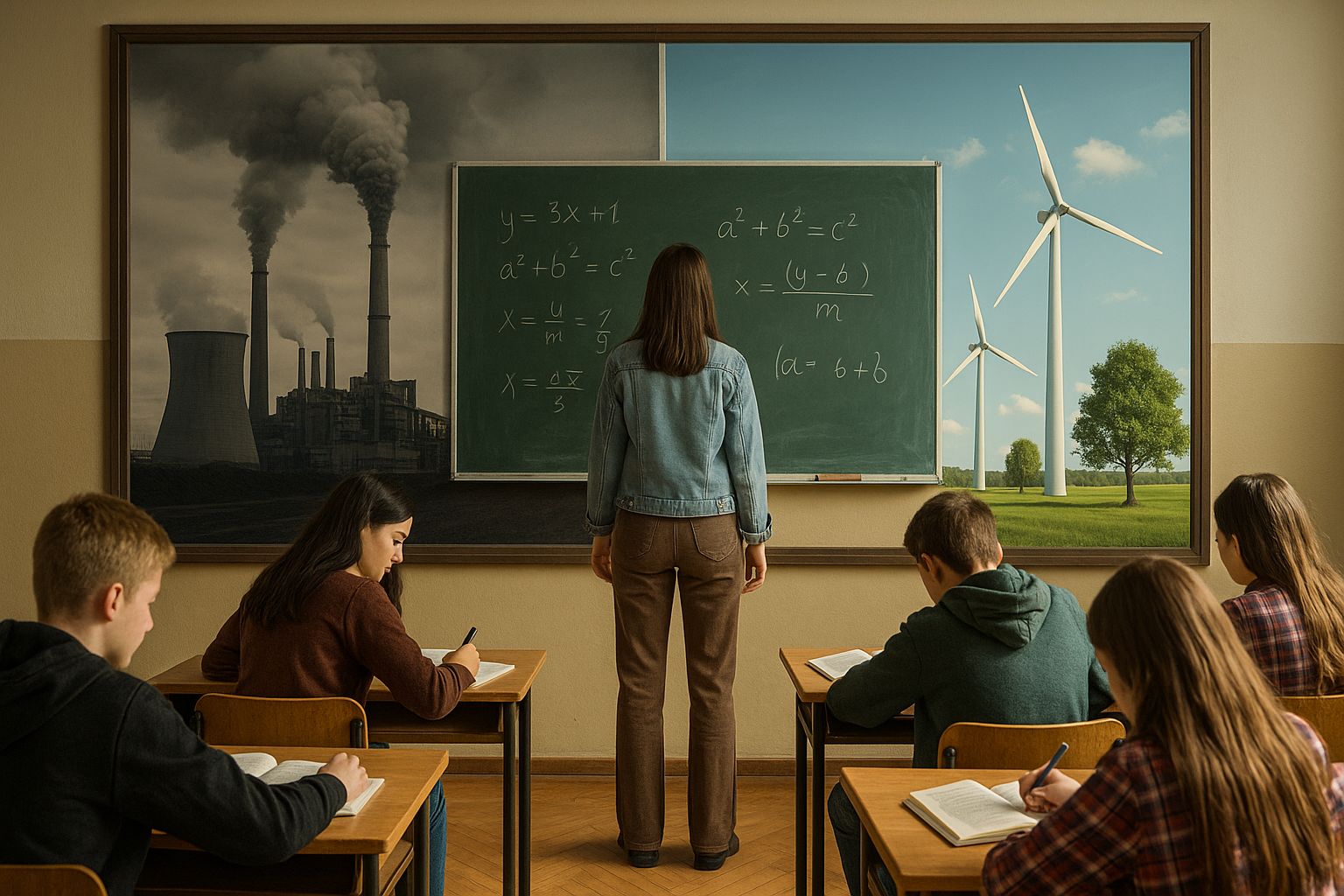

Schools, Skills and Sustainability: Serbia’s Urgent Green Transition Challenge

A World Bank study with Serbian research institutes warns that Serbia’s education and skills system must urgently adapt to the green transition, or risk deepening inequality and leaving workers behind. It calls for systemic reforms, from early schooling to higher education and reskilling to align with EU climate goals and drive an inclusive, sustainable future.

Serbia is standing at a decisive moment in its development, as the global green transition gathers momentum and demands new skills, mindsets, and policies. A recent World Bank study, prepared in collaboration with the Institute of Economic Sciences in Belgrade and the Vinča Institute of Nuclear Sciences, sets out a comprehensive picture of how the country’s education and training systems must evolve to respond to climate change, the drive for decarbonization, and the growing need for a workforce equipped for sustainability. The report highlights both the opportunities and the risks facing Serbia as it works to align with the European Union’s Green Agenda and its own pledge to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, stressing that without urgent reforms in education, research, and workforce training, the country risks leaving thousands of workers behind while slowing the pace of its climate commitments.

Climate Awareness High, But Action Still Hesitant

At the heart of the study is the recognition that education plays a dual role in the green transition: it builds public awareness and resilience while also preparing individuals with technical, cognitive, and socio-emotional skills for new types of employment. Surveys show that most Serbians acknowledge climate change is real and caused by human activity, with air pollution, rising temperatures, and extreme weather topping public concerns. Environmental protection is often rated as a higher priority than economic growth. Yet this concern is marked by contradictions: while almost all respondents want more education and training on the green transition, very few are willing to contribute through higher taxes, and the majority place the responsibility for action squarely on the government. These attitudes reveal a pressing need for schools, universities, and training systems to play a stronger role in shaping not just the skills but also the civic responsibility necessary for long-term climate resilience.

Ambitious Policies, But Gaps in Implementation

On the policy front, Serbia has made progress in adopting a suite of climate laws, strategies, and international commitments. It has an Integrated National Energy and Climate Plan, a low-carbon development framework, and alignment with the EU’s Green Agenda. However, the study finds that these policies are poorly implemented and frequently disconnected from labor market planning and education reform. Green jobs remain undefined in official policy documents, there are no systematic mechanisms for monitoring their development, and vocational training still lags in adapting to future demands. EU accession provides momentum through funding streams such as Erasmus+, Horizon Europe, and the Youth Guarantee, and international partners, including the World Bank, are extending financial and technical assistance. But aligning these resources with practical reforms in curricula, teaching, and qualifications is still a work in progress.

Education Gaps and Labor Market Pressures

The report paints a sobering picture of the weaknesses in Serbia’s human capital. According to the Human Capital Index, nearly one-third of potential is being lost due to inadequate education and health outcomes. International benchmarks like the OECD’s PISA 2022 show that Serbian students perform well below the OECD average in mathematics, reading, and science, with disadvantaged students especially at risk. These gaps are critical because foundational skills are the bedrock upon which green knowledge and advanced technical expertise must be built. Environmental education exists in fragments across science, geography, and chemistry curricula, but it remains unsystematic, donor-driven, and heavily dependent on enthusiastic teachers rather than national strategy. Teacher training, curriculum modernization, and lifelong learning opportunities are underfunded and underdeveloped, with estimates suggesting that retraining teachers alone could cost between nine and thirty million euros.

The labor market outlook is even more pressing. The green transition is expected to affect one in six Serbian workers, especially in transport, manufacturing, and carbon-intensive industries. Without targeted reskilling, nearly a quarter of a million workers could be at risk of losing their livelihoods. The cost of retraining them could exceed half a billion euros, but the report warns that the cost of inaction would be far greater in terms of unemployment, social dislocation, and stalled economic modernization.

Seeds of Progress and Innovation

Despite the systemic challenges, there are bright spots. Schools across the country are participating in initiatives like Eco-Schools, Climate Box, and Sunny Schools, which bring sustainability into classrooms through recycling, renewable energy, and climate awareness programs. Universities are beginning to offer specialized programs, such as the University of Belgrade’s Master’s in Climate Change and Adaptation, and the University of Novi Sad’s renewable energy initiatives, including solar installations and spin-off companies. Research and innovation are supported by strategies like Smart Specialization, as well as funding mechanisms like Green Innovation Vouchers and UNDP’s Innovation Challenge Calls, though stronger industry–university linkages remain essential.

Infrastructure, too, poses challenges. Around twelve percent of schools are highly exposed to floods, while others face risks from landslides and wildfires. Closing schools due to disasters has proven devastating for learning, as the COVID-19 pandemic illustrated. Retrofitting buildings, investing in green construction, and integrating renewable energy sources are presented as both urgent safety measures and visible symbols of Serbia’s green ambitions. Projects in preschools and universities have already shown the feasibility of this approach, but scaling it nationwide requires financing that blends domestic budgets, EU funds, and innovative tools such as green bonds.

Roadmap for a Just and Inclusive Transition

The study ultimately calls for a comprehensive strategy to integrate green skills into education and training. It stresses the need for a national framework, guided by interministerial cooperation, to coordinate reforms across foundational education, vocational training, and higher learning. Universal access to pre-primary education, modernization of curricula, retraining of teachers, and expansion of flexible training opportunities such as micro-credentials are all highlighted as priorities. Higher education institutions are urged to take a leading role in research, innovation, and international collaboration, positioning Serbia not just to absorb green technologies but to help shape them. The message is clear: education is not a side issue but the central pillar of Serbia’s climate strategy. If embraced, it can transform the country’s economy and society, ensuring that the green transition becomes a pathway to inclusive prosperity rather than a source of exclusion.

- FIRST PUBLISHED IN:

- Devdiscourse

ALSO READ

Contracting Carbon: The World Bank’s Blueprint for High-Integrity Climate Solutions

Carolina Rendón Named World Bank Resident Representative for Dominican Republic

World Bank Joins MADE Alliance to Drive Africa’s Digital Transformation

World Bank Urges Mongolia to Seize Mining Boom for Crucial Fiscal Reforms

World Bank Approves $50M Grant to Boost Competition and Inclusion in Tajikistan