AI moral alignment is an illusion without justification democracy and debate

The study stresses that reasonable moral disagreement is an enduring feature of pluralistic societies. Rather than attempting to suppress this diversity, AI systems should be designed to accommodate it - or at minimum, not obscure it. By failing to make room for dissent or offer mechanisms for contesting moral outputs, current AI alignment strategies risk becoming authoritarian in effect, if not in intent.

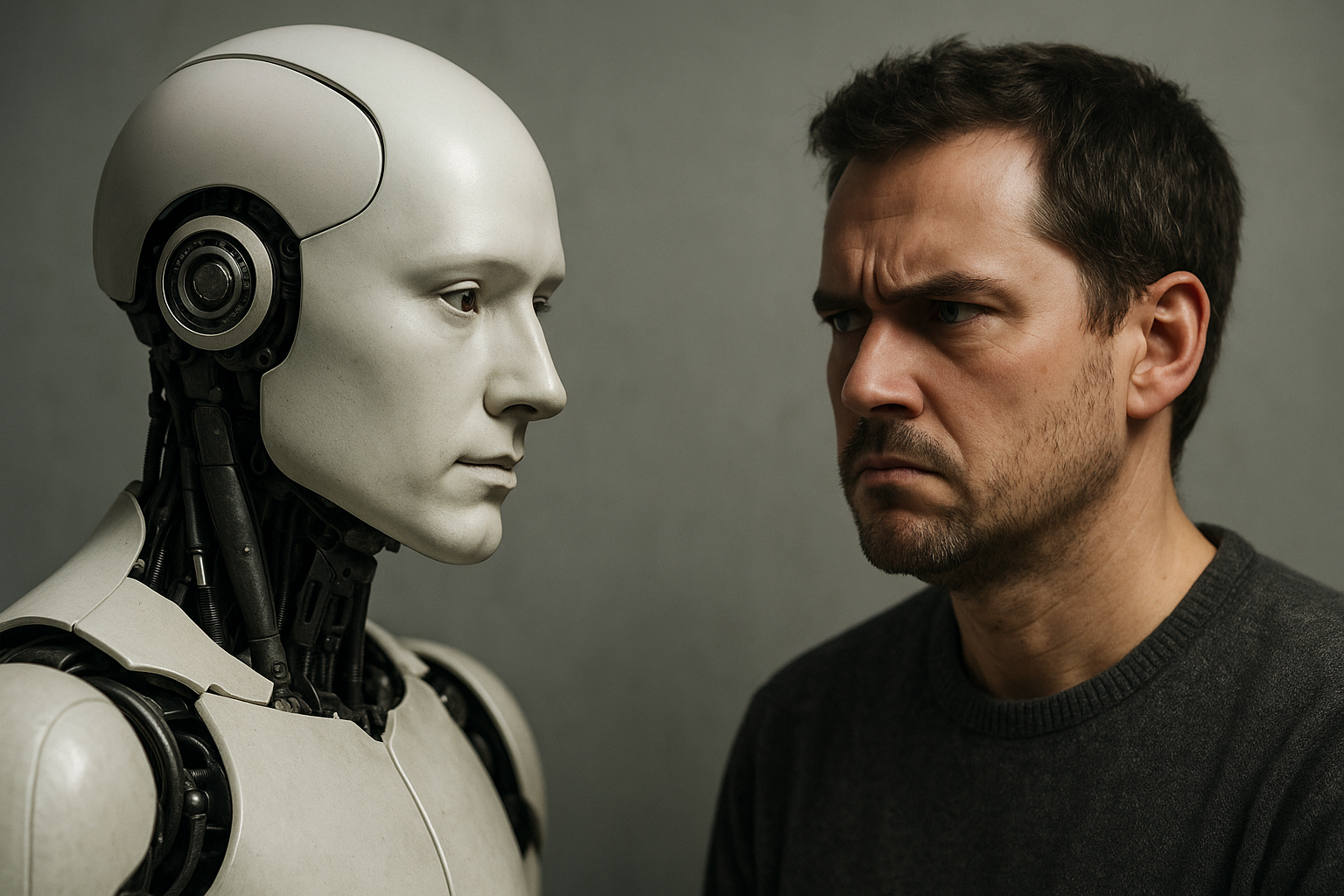

A new academic study reveals that current approaches to AI value alignment fail to adequately address the complexities of moral disagreement. Titled “Moral Disagreement and the Limits of AI Value Alignment: A Dual Challenge of Epistemic Justification and Political Legitimacy”, and published in AI & Society, the paper critically examines three dominant value alignment strategies, crowdsourcing, reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), and constitutional AI, and argues that each falls short in reconciling the diverse and often conflicting moral perspectives present in society.

The study argues that despite significant progress in making AI more responsive to human preferences, foundational challenges remain unresolved. More specifically, current alignment mechanisms do not offer sufficient epistemic justification for why AI systems’ moral outputs should be accepted as correct, nor do they ensure political legitimacy, the idea that decisions are acceptable to all who are affected by them. The authors conclude that unless AI developers confront these dual deficits, the legitimacy and safety of AI systems making moral decisions will remain fundamentally compromised.

Can AI systems justify their moral outputs?

The study assesses whether AI systems can provide epistemically sound reasons for their moral decisions. In other words, when an AI system determines that one course of action is ethically superior to another, can it offer a justification that people across varying belief systems have good reason to accept?

The authors analyze crowdsourcing-based alignment models, which aggregate human judgments into a moral consensus. While this approach can reflect majority opinion, the study argues it offers no deeper justification for why such a consensus should be taken as morally authoritative - especially in cases of deep ethical disagreement. Crowd opinion, even when statistically robust, does not necessarily equate to ethical correctness.

Reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) is also critiqued for a similar shortfall. Though RLHF allows AI to improve its outputs by learning from human preferences, these preferences are often unexamined, inconsistent, or shaped by prevailing biases. Without a framework to evaluate the moral quality of those preferences, RLHF risks reinforcing status quo norms without ever scrutinizing whether those norms are ethically defensible.

Constitutional AI, where models are guided by predefined principles or charters, such as human rights frameworks, initially appears more promising. However, the study finds that even this method lacks an adequate epistemic foundation unless it can explain why those principles are valid across moral divides. The choice of which constitution to embed, and who defines its values, remains contentious. If such principles are selected without broad, cross-cultural deliberation, they risk becoming another form of arbitrary moral authority.

What makes AI morality politically legitimate?

Beyond epistemic justification, the study explores whether the moral decisions made by AI systems are politically legitimate, that is, whether all individuals affected by those decisions have valid reasons to endorse or at least tolerate them, even when they disagree.

This question becomes urgent as AI systems are deployed in settings like content moderation, criminal justice, and healthcare - domains where decisions carry serious ethical implications. The authors argue that political legitimacy requires procedures that respect pluralism, invite public scrutiny, and can be contested or revised through participatory processes.

Crowdsourcing and RLHF, while appearing participatory, fail this test because they are typically conducted in non-transparent ways. The sample of human raters may not be demographically or ideologically representative. The process is rarely open to democratic deliberation or challenge. As a result, the AI’s values reflect a selective and opaque snapshot of human opinion rather than a politically legitimate consensus.

Constitutional AI is somewhat better equipped to satisfy procedural legitimacy, but only if the constitution itself is formed through inclusive, democratic mechanisms. In practice, many AI constitutions are developed by private companies or elite research groups without public input. This top-down imposition undermines their claim to legitimacy, particularly in multicultural societies where no single moral framework commands universal agreement.

The study stresses that reasonable moral disagreement is an enduring feature of pluralistic societies. Rather than attempting to suppress this diversity, AI systems should be designed to accommodate it - or at minimum, not obscure it. By failing to make room for dissent or offer mechanisms for contesting moral outputs, current AI alignment strategies risk becoming authoritarian in effect, if not in intent.

What must change in AI value alignment research?

The study provides a roadmap for more philosophically robust and politically legitimate approaches to AI value alignment. The authors suggest a pivot away from models that seek a singular moral truth encoded in algorithms, and toward frameworks that foreground transparency, accountability, and democratic input.

They argue that future research must grapple with the legitimacy problem, not just the performance problem. This means designing AI systems whose value outputs can be openly questioned, deliberated, and revised. It may involve integrating AI into human institutional processes, courts, councils, regulatory bodies, rather than treating AI as a standalone moral agent.

Another priority is the inclusion of moral epistemologists and political theorists in the alignment conversation. Technical improvements alone cannot resolve normative questions about what counts as a good reason, who decides, and how dissent is handled. By expanding the disciplinary scope of alignment research, the field can better respond to the democratic and ethical demands of deploying AI in morally charged domains.

The study also warns against premature convergence, the rush to settle on one alignment strategy before moral consensus is achieved. Instead of perfecting AI to reflect existing norms, researchers should create systems that remain open to ongoing moral evolution, difference, and public reasoning.

- FIRST PUBLISHED IN:

- Devdiscourse